April 25th 1915

We were awakened up about 1.30am and were told to get our equipment on as we had arrived at our destination. We were all excited, and before we fell in on deck, we had a ration of rum given to us, and we needed it for it was very cold. We then fell in on deck in the places marked out for us, and we had to make no noise, everything was done in order, no hurry or bustling.

The officer called the roll in a whisper, then we were told to disembark down the ladders into the small boats, which were waiting. I can tell you it was no easy task to climb down a ladder with a full pack up, and a sack with a pick and shovel in, and your rifle slung on your shoulder, anyhow we got into them, and it was a very tight fit (I may mention here that the Squad I was in under Sergeant-Major Pantlin were attached to the 11th Battalion).

For a short distance the boats kept in the shadow of the Man of War, and it was then I noticed we were in the first boat of our line, and that would mean we would be nearest the enemy. At last we drew away from our protection and proceeded inwards, to a place we had never seen before and we knew very little of what we had to go through before another day was over.

Now that we had left the warship we felt the tension, the silence was awful, everyone’s nerves were at a very high tension, for we were expecting every minute to be seen by the enemy. Anyhow, we went on our way slowly but surely and what drew my attention was a very bright star in the sky, that shone out so brightly and it seemed to be a magnet and was drawing us towards it.

By this time we could just make out the distant hills and we must have been only about a hundred yards off the shore, when the Commander of the Naval Pinance sang out the words “Tell the Colonel these devils have brought us a mile too far North” (what he meant then I did not know, but since I have learnt that it was the strong current that was running that carried us out of our way).

No sooner were the words out of his mouth, then a bright light shone out from the shore and one shot rang over the hills. We knew then that we were seen by the Turks and we were told to pull for our lives to the shore, by the time we had dipped the oars into the water, the bullets were hitting the boats and the water wholesale, then we were told to get out, and get ashore the best way we could, every man for himself. I can tell you it was cruel to see our lads dropping into the boats, for they had machine guns trained onto us besides their rifle fire.

It was just Hell let lose, nothing short of murder, to see our boys go down like sheep, it made your blood boil, and then that is the time you get mad with excitement, and you are only out to kill or be killed, to avenge the pals who you have loved like brothers. I along with my chums were lucky to reach the shore after a few attempts to wade through water up to the neck. It was the coldest Turkish bath I ever had. There were quite a number of our fellows drowned in trying to get ashore with their packs pulling them down.

After a while we reached the shore, and managed to get under cover, we threw off our packs, for we were wet to the skin. We rested awhile, then crawled along on our stomachs to join the boys, all the time the bullets were singing their death song about our ears, but we did not care for we were at high pitch.

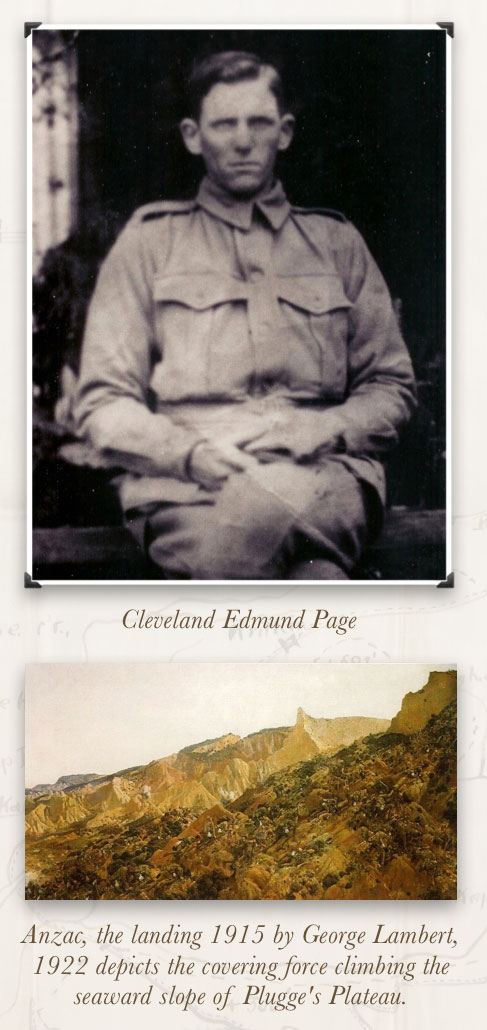

No sooner did we come into view of the enemy, when they opened out with a very deadly fire. One of my pals Cleve Page was hit in the head, killed stone dead, he dropped at my feet; and I vowed vengeance on his slayers. Cook and me kept on, and joined the rest. Then the order was given to fix bayonets; and drive the Turks out, which we did with a vengeance. I will never forget that charge, for our boys started to coo-ee for all they were worth and gave them the cold steel.

What happen is too awful to put down, for even should I put it down no one would realise what war is like unless they have been in the thick of it, as we were then, and at what cost taking that hill, we took the first one, then the second, and we must have gone five miles that morning before nine. We had no officers hardly left to tell us what to do, and I know that some of our fellows were killed by shells from HMS Queen Elizabeth but it could not be helped.

The cries of the wounded, the moans of the dying, it was awful and they were giving us some shells to go on with, and we were suffering because we had no head cover. We were kept on the defensive all day, then night fell, our first night in the trench, as soon as it was dark we dug in, so that there would be a little shelter for us on the morrow.

I never passed such a night. Things would be fairly quiet, with the searchlights playing about from the war ship. When one of the boys would fancy he saw something move, and would let fly. That would start all the line blazing away. We had no rest for our nerves were too high strung to rest and we had to just keep banging away.